Tos Through Deck Transport New Tos Design

Opinion

Author Interviews

'Moby-Duck': When 28,800 Bath Toys Are Lost At Sea

'Moby-Duck': When 28,800 Bath Toys Are Lost At Sea

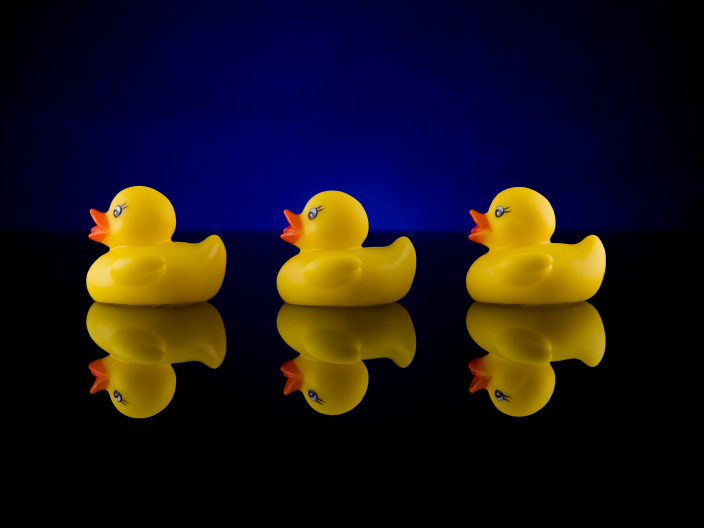

In 1992, 28,800 rubber ducks were lost at sea. What happened to them is the subject of Donovan Hohn's book Moby-Duck. Jose Gil/iStockphoto.com hide caption

toggle caption

Jose Gil/iStockphoto.com

In 1992, 28,800 rubber ducks were lost at sea. What happened to them is the subject of Donovan Hohn's book Moby-Duck.

Jose Gil/iStockphoto.com

In 1992, a cargo ship container tumbled into the North Pacific, dumping 28,000 rubber ducks and other bath toys that were headed from China to the U.S. Currents took them, and news reports said some may have eventually reached Maine and other shores on the Atlantic.

Thirteen years later, journalist Donovan Hohn undertook a mission: He wanted to track the movements of the wayward ducks, from the comfort of his own living room.

"I figured I'd interview a few oceanographers, talk to a few beachcombers, read up on ocean currents and Arctic geography and then write an account of the incredible journey of the bath toys lost at sea," he tells Fresh Air's Dave Davies. "And all this I would do, I hoped, without leaving my desk."

But Hohn's research led him on an odyssey that took him from Seattle to Alaska to Hawaii — and then onto China and the Arctic. He details the journey — via plane, foot and container ship — in Moby-Duck: The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea and of the Beachcombers, Oceanographers, Environmentalists and Fools, Including the Author, Who Went in Search of Them.

Moby-Duck

By Donovan Hohn

Hardcover, 416 pages

Viking Adult

List Price: $27.95

Read An Excerpt

Some of the ducks, says Hohn, made their way to the coast of Gore Point, Alaska, a remote isthmus at the southern tip of Kachemak Bay State Park. Hohn obtained his own rubber duck after visiting the isthmus with the Gulf of Alaska Keeper, a group of conservationists who wanted to clean up the debris along the coast.

"They set out on a pretty heroic undertaking, because to get this [ocean debris] out of the wilderness required 2 to 3 months of people camping and packing [the debris] up in a bag, and eventually an airlift," he says. "But while I was out there with them, toys were found. I found a plastic beaver. And another beachcomber found a duck and had mercy — he gave it to me."

The Plague Of Plastic In The Ocean

While tracking down the path of the rogue ducks, Hohn also confronted the plague of accumulating plastics in the ocean.

"When I set out following these toys, I didn't expect it to turn into an environmental story, but I very quickly learned ... that unlike the flotsam of ages past, the flotsam of today — much of it plastic — persists," he says. "It lasts visibly for decades and chemically for centuries because it doesn't biodegrade."

There are certain parts of the ocean where currents converge and spiral inward, collecting what's floating on the surface, Hohn says. Called convergence zones or "garbage patches," these parts of the ocean contain trash, plastic and toys — whatever happens to get sucked in while floating past.

Donovan Hohn's work has also appeared in Harpers, The New York Times Magazine and Outside Magazine. He is a features editor at GQ. Beth Chimera/Viking Adult hide caption

toggle caption

Beth Chimera/Viking Adult

Donovan Hohn's work has also appeared in Harpers, The New York Times Magazine and Outside Magazine. He is a features editor at GQ.

Beth Chimera/Viking Adult

"When I first heard the phrase 'garbage patch,' I imagined something dense," he says. "I initially imagined it as a floating junkyard, and you'd have to poke your way through it with a paddle if you're in a kayak. But it's not like that. You can't take a picture of it because that doesn't exist. What does exist is a whole lot of plastic out there, but it's spread out over millions of miles of ocean. And some of it floats on the surface where you can find it. And some of it floats just below the surface. And eventually all of it will photodegrade, so much of it is so small you're not going to be able to see it with the naked eye."

These tiny pieces of plastic — and substances that adhere to the plastics — can then enter the food chain.

"We know that in the marine food web, there is an alarmingly elevated contaminant burden in species at the top of the food web," he says. "What role plastic plays in that is an ongoing area of study."

Interview Highlights

On the importance of beachcombers

"There are people who do beachcombing for different reasons, but there's a community — a bit like avid bird-watchers — for whom it is more than just a pleasurable recreational thing to do when you go to the seashore. [For them] it's a hobby and a hunt. [There's a magazine] called Beachcombers Alert [that] puts the beachcombers on alert for Nikes or whatever — because there was a spill that's been reported — and then people go out and find them. So you not only have the thrill of discovering a surprise or treasure, but you also have the chance of, like on a scavenger hunt, finding something that you're looking for that actually might serve some scientific purpose."

On the importance of the spills to the scientific community

"They do show us something. The currents have been compared to rivers in the sea, but ocean currents don't flow like rivers between two banks — they meander [and] they change seasonally and are, in a way, more mysterious than one might think. They're almost comparable to the wind the way that they move and the way that they vary. By following flotsam spills, you do have useful data to show us the movement of the currents and how they change."

On the worst shipping container disaster in modern history

"[A ship named APL China] was traveling from Far East to the Pacific Northwest [in 1998] and it lost 407 containers overboard in a single night [after a possible typhoon]. The photographs that were taken when it was in port are pretty dramatic. ... This ship came in and it looked ravaged. Most of the rows of containers had toppled like dominoes. Some of them had been pancaked flat by the ones on top of them. Some containers were just missing — swept overboard. So it was a ruin when it staggered into port."

Excerpt: 'Moby-Duck'

Moby-Duck

By Donovan Hohn

Hardcover, 416 pages

Viking Adult

List Price: $27.95

At the outset, I felt no need to acquaint myself with the six degrees of freedom. I'd never heard of the Great North Pacific Garbage Patch. I liked my job and loved my wife and was inclined to agree with Emerson that travel is a fool's paradise. I just wanted to learn what had really happened, where the toys had drifted and why. I loved the part about containers falling off a ship, the part about the oceanographers tracking the castaways with the help of far-flung beachcombers. I especially loved the part about the rubber duckies crossing the Arctic, going cheerfully where explorers had gone boldly and disastrously before.

At the outset, I had no intention of doing what I eventually did: quit my job, kiss my wife farewell, and ramble about the Northern Hemisphere aboard all manner of watercraft. I certainly never expected to join the crew of a fifty-one-foot catamaran captained by a charismatic environmentalist, the Ahab of plastic hunters, who had the charming habit of exterminating the fruit flies clouding around his stash of organic fruit by hoovering them out of the air with a vacuum cleaner.

Certainly I never expected to transit the Northwest Passage aboard a Canadian icebreaker in the company of scientists investigating the Arctic's changing climate and polar bears lunching on seals. Or to cross the Graveyard of the Pacific on a container ship at the height of the winter storm season. Or to ride a high-speed ferry through the smoggy, industrial backwaters of China's Pearl River Delta, where, inside the Po Sing plastic factory, I would witness yellow pellets of polyethylene resin transmogrify into icons of childhood.

I'd never given the plight of the Laysan albatross a moment's thought. Having never taken organic chemistry, I didn't know and therefore didn't care that pelagic plastic has the peculiar propensity to adsorb hydrophobic, lipophilic, polysyllabic toxins such as dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (a.k.a. DDT) and polychlorinated biphenyls (a.k.a. PCBs). Nor did I know or care that such toxins are surprisingly abundant at the ocean's surface, or that they bioaccumulate as they move up the food chain. Honestly, I didn't know what "pelagic" or "adsorb" meant, and if asked to use "lipophilic" and "hydrophobic" in a sentence I'd have applied them to someone with a weight problem and a debilitating fear of drowning.

If asked to define the "six degrees of freedom," I would have assumed they had something to do with existential philosophy or constitutional law. Now, years later, I know: the six degrees of freedom — delicious phrase! — are what naval architects call the six different motions floating vessels make. Now, not only can I name and define them, I've experienced them firsthand. One night, sleep-deprived and nearly broken, in thirty-five-knot winds and twelve-foot seas, I would overindulge all six — rolling, pitching, yawing, heaving, swaying, and surging like a drunken libertine — and, after buckling myself into an emergency harness and helping to lower the mainsail, I would sway and surge and pitch as if drunkenly into the head, where, heaving, I would liberate my dinner into a bucket.

At the outset, I figured I'd interview a few oceanographers, talk to a few beachcombers, read up on ocean currents and Arctic geography, and then write an account of the incredible journey of the bath toys lost at sea, an account more detailed and whimsical than the tantalizingly brief summaries that had previously appeared in news stories. And all this I would do, I hoped, without leaving my desk, so that I could be sure to be present at the birth of my first child.

But questions, I've learned since, can be like ocean currents. Wade in a little too far and they can carry you away. Follow one line of inquiry and it will lead you to another, and another. Spot a yellow duck dropped atop the seaweed at the tide line, ask yourself where it came from, and the next thing you know you're way out at sea, no land in sight, dog-paddling around in mysteries four miles deep. You're wondering when and why yellow ducks became icons of childhood. You want to know what it's like inside the toy factories of Guangdong. You're marveling at the scale of humanity's impact on this terraqueous globe and at the oceanic magnitude of your own ignorance. You're giving the plight of the Laysan albatross many moments of thought.

The next thing you know, it's the middle of the night and you're on the outer decks of a post-Panamax freighter due south of the Aleutian island where, in 1741, shipwrecked, Vitus Bering perished from scurvy and hunger. The winds are gale force. The water is deep and black, and so is the sky. It's snowing. The decks are slick. Your ears ache, your fingers are numb. Solitary, nocturnal circumambulations of the outer decks by supernumerary passengers are strictly forbidden, for good reason. Fall overboard and no one would miss you. You'd inhale the ocean and go down, alone. Nevertheless, there you are, not a goner yet, gazing up at the shipping containers stacked six-high overhead, and from them cataracts of snowmelt and rain are spattering on your head. There you are, listening to the stacked containers strain against their lashings, creaking and groaning and cataracting with every roll, and with every roll you are wondering what in the name of Neptune it would take to make stacks of steel — or for that matter aluminum-containers fall. Or you're learning how to tie a bowline knot and say thank you in both Inuktitut and Cantonese.

Or you're spending three days and nights in a shabby hotel room in Pusan, South Korea, waiting for your ship to come in, and you're wondering what you could possibly have been thinking when you embarked on this harebrained journey, this wild duckie chase, and you're drinking Scotch, and looking sentimentally at photos of your wife and son on your laptop, your wife and son who, on the other side of the planet, on the far side of the international date line, are doing and feeling and drinking God knows what. Probably not Scotch. And you're remembering the scene near the end of Moby-Dick when Starbuck, family man, first officer of the Pequod, tries in vain to convince mad Ahab to abandon his doomed hunt. "Away with me!" Starbuck pleads, "let us fly these deadly waters! let us home!"

And you're dreaming nostalgically of your former life of chalkboards and Emily Dickinson and parent-teacher conferences, and wishing you could go back to it, wishing you'd never contacted the heavyset Dr. E., or learned of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, or met the Ahab of plastic hunters, or the heartsick conservationist or the foulmouthed beachcomber or the blind oceanographer, any of them. You're wishing you'd never given Big Poppa the chance to write about Luck Duck, because if you hadn't you'd never have heard the fable of the rubber ducks lost at sea. You'd still be teaching Moby-Dick to American teenagers. But that's the thing about strong currents: there's no swimming against them.

The next thing you know years have passed, and you're still adrift, still waiting to see where the questions take you. At least that's what happens if you're a nearsighted, school-teaching, would-be archaeologist of the ordinary, with an indulgent, long-suffering wife and a juvenile imagination, and you receive in the mail a manila envelope, and inside this envelope you find a dozen back issues of a cheaply produced newsletter, and in one of those newsletters you discover a wonderful map — if, in other words, you're me.

Reprinted by arrangement with Viking, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from Moby-Duck by Donovan Hohn. Copyright 2011 by Donovan Hohn.

Moby-Duck

The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea and of the Beachcombers, Oceanographers, Environmentalists, and Fools, Including the Author, Who Went in Search of Them

by Donovan Hohn

Hardcover, 402 pages |

purchase

Buy Featured Book

- Title

- Moby-Duck

- Subtitle

- The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea and of the Beachcombers, Oceanographers, Environmentalists, and Fools, Including the Author, Who Went in Search of Them

- Author

- Donovan Hohn

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Amazon

- iBooks

- Independent Booksellers

Tos Through Deck Transport New Tos Design

Source: https://www.npr.org/2011/03/29/134923863/moby-duck-when-28-800-bath-toys-are-lost-at-sea

0 Response to "Tos Through Deck Transport New Tos Design"

Post a Comment